One of Ami Ayalon’s favorite words in public lectures may be litzlol, to dive. Not surprising given his storied military career, first as a commando in Flotilla 13, akin to the Navy SEALS, and eventually as commander of Israel’s navy. But these days he means taking a deeper look at the conflicts that bind Israel and Palestine like seaweed.

One of Ami Ayalon’s favorite words in public lectures may be litzlol, to dive. Not surprising given his storied military career, first as a commando in Flotilla 13, akin to the Navy SEALS, and eventually as commander of Israel’s navy. But these days he means taking a deeper look at the conflicts that bind Israel and Palestine like seaweed.

His new memoir, “Friendly Fire: How Israel Became Its Own Worst Enemy and the Hope For Its Future,” could never have been a conventional autobiography of an Israeli leader.

Although it depicts the kinds of events you might expect–his upbringing in kibbutz, the 1969 battle on Egypt’s Green Island where he nearly lost his life and won the Medal of Valor, his rise to naval commander and years as director of the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, in the wake of Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, his time in the Knesset–it’s far from a “greatest hits” doorstop. Instead, Ayalon reconsiders specific events that led to his growing uneasiness with the idealized “build the land” version of Zionism he was raised with and the more complex reality he has faced.

“I’m 76 years old now, and for the last several years, I’ve been trying to understand myself. In many cases, I’m a minority, even among my friends and even sometimes within my family. But I think we are heading the wrong way. I tell my story for two reasons,” says Ayalon. “First, people have to understand who I am in order to listen to me, and who I am is the people whom I’ve met, the stories I was told and the events that I’ve been through. Second, the main message of the book, which is my main activity today, is to convince the younger generation in Israel, the people who are still asking questions, that there is a way to a better future.”

From anyone else, a statement like this might sound academic or naïve, but his conclusions are built directly on his experience leading the agency most responsible for fighting terror in Israel and the Palestinian territories and on his work with Palestinian colleagues to quell violence.

In 2000 he retired from the Shin Bet, turning down Ehud Barak’s invitation to join him at the Camp David Accords, and after Arafat stomped off, refuted Barak’s famous declaration that there was no Palestinian negotiating partner. Since then, Ayalon has become one of the leading voices in Israel calling for negotiating more constructively with the Palestinians for a two-state solution. He maintains that Israel’s hardline tactics undermine its negotiating position, repeatedly weaken its own security and even threaten its future.

“We are sending our children to fight a war that, if we win and our eastern border becomes the Jordan, this is the end of Zionism, the end of Israel as a Jewish democracy. It’s a huge paradox. But if we are not the majority, we don’t have the right—we don’t have the power—to dictate the national culture, the language, the story, the calendar…and some of our children are dying for it. Aside from the Palestinians who are dying, our children are dying.”

How of all people did he get to this point?

Ayalon was born on Kibbutz Ma’agan, on the Sea of Galilee, in 1945. His parents, fervent Zionists, had come from Romania in the 1930s. “I can imagine my father telling his father that he’s not a Jew anymore because he’s a Zionist. They called themselves Hebrews—’Jews speak Yiddish. Zionists speak Hebrew!’ And you know my father, when he came to Israel, he almost didn’t know Hebrew, so for several months it was very difficult for him to manage.” His father gave up his only keepsake, a family ring, to support the struggling young kibbutz. “They were very stubborn…In our terms today they were very poor. But they had a mission to create a state for the Jewish people which was in danger, although they didn’t know it.”

His parents didn’t talk openly about the past. “They didn’t talk about the Shoah, the Holocaust. They didn’t talk about their families, those who died and those who survived and stayed in Europe. They were socialists—they erased their past, 2000 years of history, to create a new future. It wasn’t evolution, it was revolution—you erase.”

Nevertheless, when his father Yitzhak was in his 80s, Ayalon suggested he write down some of his stories for the grandchildren and it turned out Yitzhak had thrown himself into redressing the aftermath of the Shoah. From 1945-48, his father worked in Hungary smuggling Jewish refugees into Palestine under Britain’s nose. A few years later, Yitzhak took the family to South America for two and a half years, primarily to encourage youth aliyah, but he also helped guard Eichmann before his transfer to Israel for trial. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Ayalon says, “He was the first secretary in our embassy in Romania. He used to meet with Ceaucescu every week. He used to bring a suitcase with cash in exchange for letting Jews emigrate. I was in the navy then so we couldn’t visit him, it was behind the Iron Curtain.”

“I love this story,” Ayalon says of his father’s recollections, “but there are still a lot of things we don’t know and should. What I learned, what I believe came from him, is that we owe something. We are members of the community and we have a great responsibility on our shoulders—for security or whatever. The concept of settlement and security was a concept of my childhood and enabled us to create this state.”

Ayalon can’t pinpoint when his own vision of Zionism and security shifted.

When he started as a Flotilla 13 commando in 1963, he says, “We went to war, it was an adventure. We killed, we lost friends, but everything was very, very clear. Reality was painted in black and white: we are the good guys, they are the bad guys. All we have to do is defend the good guys and kill the bad guys. All the rest is technology, and we are great at technology. Later it became—and you’ll see it in the book—when we went to battle, we didn’t meet soldiers, we met civilians, in refugee camps, in Lebanon and Syria.”

After one operation in Lebanon, Ayalon suddenly halted his unit’s retreat and had his medical officer treat a boy who’d been caught in the crossfire. “For me, it was obvious, okay, he’s not an enemy anymore. I don’t know what he was before, but he’s wounded; the idea is not to kill the people.” He still wasn’t sure he’d done the right thing. “In a way, I endangered my people. I started to think about it only much later.”

During the first Intifada, Ayalon was driving through a refugee camp when a teenager threw stones at his jeep. “Like many Israelis, I began to think, something’s wrong here. ‘We are liberators, this land is ours,’ our parents told us. I think it only came to me then that okay, we are liberators, it is ours, but in these places are millions of people who see us as occupiers, as conquerors, they don’t see us as liberators.”

Interwoven with these incidents are the vivid personal conversations that have shaped his thinking over the years. There are high-level discussions, often disputes, with military superiors and the political leaders he served—Eitan, Rabin, Peres, Barak—that nevertheless have the informal feel of family arguments. Ayalon meets with Jewish settlers, both moderate and extremist, to his wife’s dismay, and consults with friends, including novelist Meir Shalev and—another seeming paradox—several of Yasir Arafat’s high-level officers with whom he had coordinated intelligence and security operations at the Shin Bet.

“When I came to the Shin Bet is the first time I met people who were former terrorists. They sat in our jails for years. [Arafat’s security chiefs] Jibril Rajoub, Mohamed Dahlan, they were terrorists during the first Intifada. And I meet them—and they are human beings,” he shrugs, acknowledging that they all had painful differences to bridge in the shifting climate after Oslo.

“It was not difficult to shake the hand of Jibril Rajoub. People said, ‘But he killed an Israeli!’ But I killed many more people who had been my enemies, and still I believe that I can be part of a peace process. We need to think about how we can not go on killing each other for the next 40 years…I only came to the Shin Bet because Rabin was assassinated, but his assassin was a Jewish terrorist. We felt that we were fighting together against terrorist organizations—on both sides. And we became friends. Jibril has visited my house, he knows my wife and children, I know his children.”

He found it more difficult convincing prime ministers to cultivate trust with Arafat and his successors but says, “It’s very easy to blame politicians. I’ve been there. It’s not been my greatest success, let’s admit…Political power is not in the hands of the politicians anymore, it’s somewhere in the street. It doesn’t mean the people in the street know what to do with it.”

In 2002 Ayalon partnered with Professor Sari Nusseibah, then president of Al Quds University and Arafat’s top official in Jerusalem, to publish a one-page framework with just six key points for a mutual peace agreement and circulate it as a petition. “The idea was to show Israelis that there are Palestinians who believe in the two-state solution and vice versa. And to create this power for the leaders, because ultimately the leaders are afraid [of losing the next election].” The petition gathered nearly half a million signatures in support, both Palestinian and Israeli. “So there is huge power within civil society once we know how to get organized.”

Ayalon helped organize and was featured in the Oscar-nominated 2012 documentary “The Gatekeepers,” in which all six living Shin Bet directors spoke out urging a genuine two-state solution for Israel’s security, and co-founded the Blue White Future think tank to generate and present new ideas for advancing it.

His eye is still firmly on the future, despite the enormous political obstacles today, including the repeated stalling of parliamentary elections in both Israel and Palestine and the rash of violence in May. “The last two chapters are the idea for which ‘Friendly Fire’ was written and the topic on which I lecture to young people in Israel.”

In those chapters, Ayalon meets privately with two philosophers who have inspired him: one Israeli, Chaim Gans, whose writings argue for Israelis to reevaluate the past and redefine Zionism to value people over landmarks, and the other Dr. Sari Nusseibah, Ayalon’s longtime friend and Palestinian partner who has taken many setbacks and keeps working toward a future in which both peoples can thrive. “These conversations clarify how achievable this is and how painful a price we shall have to pay on the way to ensuring our security and identity,” Ayalon says, but his message to younger Israelis is that there is hope if they are willing to work for it. “After all, ‘If you will it, this is not a dream’ was the founding idea for the establishment of Israel.”

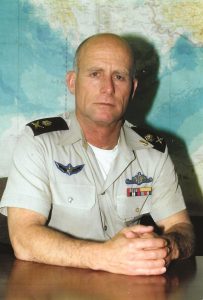

Admiral (ret.) Ami Ayalon will present his book “Friendly Fire” virtually at the 2021 Jewish Book Festival on Sunday, October 31 at noon. To learn more, register and order books, go to www.jewishsgpv.org/jewish-book-festival or call the Jewish Federation office at 626-445-0810.

Deborah Noble is a contributing writer to Jlife magazine.