In the late 19th century, a young Orthodox rabbinical student living in the north of France packed away his books and traveled to Paris – permanently leaving the Jewish community. Coming from a long line of rabbis and scholars, this was clearly a difficult and controversial decision; one that resulted not just in his loss of Judaism but the loss of his entire community. Emile Durkheim would go on to introduce a new school of thought, one where group cohesion and social structure would be at the center of study, underscored by a radical suggestion that the results of this type of study would be able to explain everything about our society today.

Widely recognized today as the father of modern sociology, Durkheim would posit a social view of religion which placed the community at the center of religious life, not G-d. Every religious community, Durkheim explained, has some realm which they deem holy – be it a totem, G-d, a temple, etc. But holy, in whichever form it arises, is actually just the community’s way of worshiping itself along with the social cohesion and moral contract between its own members. Ergo G-d and religious values are simply the community implicitly worshiping itself. Thus religion, according to the Durkheimian view, is fully reducible to a series of social interactions, without which all religions would quickly collapse.

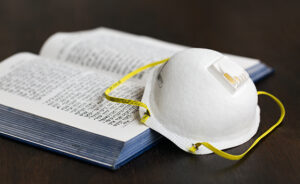

But this view is understandably a fundamental challenge to both traditional religious belief and, more currently pressing, our ability to remain connected with Judaism during coronavirus sans immediate community. In other words, if Judaism can simply be reduced to a community and a social schema, then in a time of social distancing how can one continue on as a Jew?

This question has shaken the core of many Jewish organizations as they attempt to shift from in-person social programming into the often impersonal online world of social media and video conferencing. In fact, Mordechai Kaplan, the intellectual founder of the JCC and eventually Reconstructionist Judaism, was heavily influenced by Durkheim’s work, which led him to believe that Judaism needed social centers disconnected from explicit religious theology. An institutional concept that has truly bolstered the American Jewish community – but are also necessarily tethered to a community. However, I’d like to suggest that while this problem is something that strikes at the heart of Jewish organizations, it isn’t a big problem for Judaism itself.

There certainly is a strong social and communal element to Judaism, but I believe that Durkheim was wrong and overly reductionist in his view of religion, specifically when it comes to Judaism. Judaism contains a system of ideas, ethics, and beliefs that intertwine, bolster, and challenge each other in a way that converges into what we call Jewish tradition. The biblical stories with their complex ethical issues, the intricacy of Talmudic reasoning and law, the infinite intellectual and spiritual search into attempting to “know G-d”, the motifs of exile and redemption that equip us with everlasting hope and moral imperatives- these are all parts of Judaism and parts that remain in existence even if we subtract the community. More importantly for us, these are parts of Judaism that can be taken advantage of even while social distancing.

In the past two months I have offered a series of online Jewish classes for college students in the community where I serve as the Hillel rabbi, and for Temple Beth Tikva where I serve as a rabbinic fellow. I have implored my students to spend this time discovering aspects of Judaism that may be overlooked when focusing solely on the social aspects. People who have never before opened the Talmud have begun to add their voices to the millennium old discussion, students who may not be familiar with the history of modern Israel have tuned in for weekly discussions about the Jewish state, and scores of individuals have contacted me asking for ways to further engage with Jewish learning.

The coronavirus should be seized as an opportunity for us to truly reflect on our values vis-a-vis Judaism. Is Judaism simply a social group, one that can be replaced with political involvement, a sports team, or a tight-knit friend group – or is there something deeper in this ancient tradition – something that can thrive even as we sadly can’t congregate and be together during these unprecedented times?

There is much to say about the answer to this question throughout our 3000+ year intellectual and ethical tradition. Now that we need to be taking a step back from the social parts of Judaism, rest assured that there are many other components waiting.

Daniel Levine is a contributing writer to Jlife magazine and a senior Jewish educator for Hillel. His email is Dlevine21@gmail.com.